The #BrokenRecord movement's quest to "fix" the music industry (and why they are wrong)

Artists don't make a lot of money on Spotify because Spotify doesn't make a lot of money.

Some artists want Spotify to pay them more money. The truth is that Spotify doesn’t have the money they want. In fact, the entire recorded music industry doesn’t have the money. The only solution is to try selling something new in addition to music.

Meet #BrokenRecord

The COVID-19 lockdowns eliminated much of musicians’ income by preventing them from performing live gigs and the decline in public performance royalties by businesses no longer playing music in their venues.

In response, Tom Gray—a musician and a Board Director of the Ivors Academy—launched the #BrokenRecord movement to highlight the realities for working musicians. Ivors Academy chairman Crispin Hunt and CEO Graham Davies are also notable leaders of the movement.

At the start of the movement, the leaders were careful not to vilify any individual music company nor make any specific demands that could be rejected. Instead, they focused on raising awareness of how the music industry worked attracting the attention of government regulators.

They have had some notable successes on that front. The UK Parliament Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee (DCMS) opened an inquiry into the economics of music streaming. Tom Gray also submitted a seven-page written testimony to the Committee and Ivors Academy submitted recommendations for new regulations.

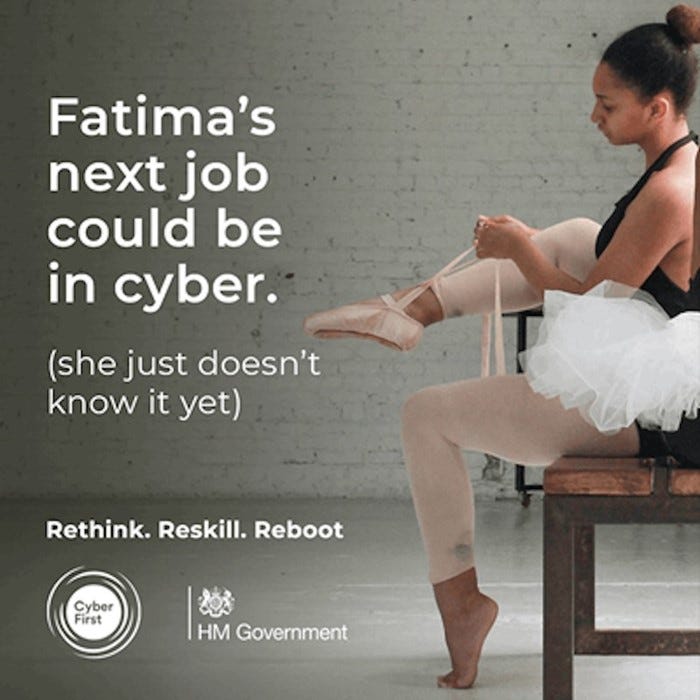

So far, the UK Government has been attentive but not all musicians feel the love. UK Chancellor Rishi Sunak suggested that artists consider retraining for other jobs—sparking outrage among musicians until he said he was misquoted. Sunak’s comments were echoed by the UK Government’s disastrous “Rethink. Reskill. Reboot” campaign that offended artists by implying they should get jobs in cybersecurity.

What #BrokenRecord gets wrong

Most of the #BrokenRecord Campaign’s complaints are legitimate—especially the ones that they direct at record labels and music publishers. But their characterization of Spotify1 as the industry’s Great Satan and their implication that Spotify could be paying artists more are false.

As the #BrokenRecord movement grew during 2020, the movement abandoned its neutral tone for one that is increasingly focused on pressuring Spotify to pay even more in royalties to rightsholders2. The movement’s exact criticisms of Spotify are clearly outlined in op-eds by Nadine Shah and James Hall. And while Gray has largely avoided suggesting an exact value for the new royalty rate, the similar movement Justice at Spotify has called for Spotify’s payout to rise from $0.0038 per stream to $0.01 per stream—more than a 2.6x hike.

1. Streaming saved the music industry from piracy—recovering money that would have been lost

Many of the artists supporting the movement began their music careers in the cash-rich era of the compact disc, and are naturally shocked by what happened to the music industry since.

The American recorded music industry’s revenues (as measured by the RIAA) declined continually from 1999 to 2015—and the decline was only reversed with paid streaming. The income that recording artists miss from the era of the CD simply no longer exists. Consumers around the world have collectively decided not to pay for music. The fact that services like Spotify and Apple Music have been able to partially reverse this trend is nothing short of a miracle.

2. Spotify can’t afford to pay rightsholders more

Spotify is a marketplace for music. None of the music belongs to them and they have little pricing power over it. Rightsholders determine how much their music should cost in negotiation with Spotify, and listeners decide how much to pay Spotify—or whether to simply pay nothing and listen to ads.

There are three barriers to Spotify being able to pay artists more:

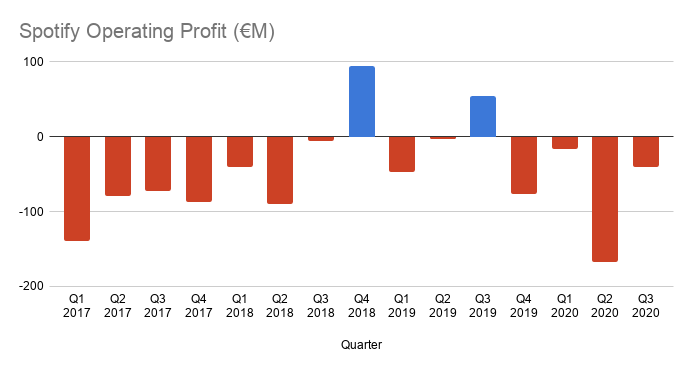

Losses. Not profits. Profitability has been a struggle for Spotify3. In financial statements from Q1 2017 to Q3 2020, Spotify has only reported an operating profit twice—having posted operating losses in every other quarter reported.

Low average payouts per artist. Kim Bayley, CEO of the Entertainment Retailers Association, argued against some of the #BrokenRecord movement’s claims in a piece titled “You don't mend a #BrokenRecord by smashing the record player.” She points out that Spotify allows many low-earning artists on their platform whose music would never be distributed by physical record store chains. These artists make only a few dollars per year—dramatically lowering the average payout across all Spotify artists. Even if Spotify sacrificed their (roughly 25%) gross margin into royalties for artists, it would hardly make a difference in terms of offering a living wage to low-earning artists.

Bargain-basement subscriptions. The average price of an individual Spotify subscription is likely to go down. We can expect most of Spotify’s future user growth to be in India or Latin America where listeners’ ability to pay is even lower. Spotify recently launched 'Premium Mini' subscriptions in India at ₹7 INR ($0.10 USD) per day or ₹25 INR ($0.34 USD) per week. The low prices will likely help Spotify grow its marketshare, but there will be even less room for Spotify to pay artists even more per stream.

If not #BrokenRecord, then what?

The #BrokenRecord activists are correct about a lot of things in the music industry, especially about the toxic relationship between artists and their labels/publishers. But where they went wrong is by starting a political movement around squeezing nonexistent pennies out of Spotify. Even if their campaign somehow succeeded, how many more artists would be meaningfully better off?

(Hint: almost none.)

Instead, we should consider that humans may not have paid to hear music for most of human history and that the revenues earned from vinyl and CDs represent a temporary asset bubble whose conditions cannot recur in a newly digital world.

In the twenty-first century, from a revenue perspective, people think of paid streaming as the replacement for CD album sales. But from a strategic perspective, streaming is the replacement for radio airplay—a non-rival loss leader that facilitates discovery and demand for something else. Spotify now even offers advertising services to record labels [1,2].

This begs the question—from a strategic perspective, what can replace the lost CD album sales? Here are some awful guesses:

Live performances. For generations, many artists made the bulk of their income from touring—which has been disrupted due to COVID-19. Some artists have managed to replace some of that lost revenue with online virtual concerts through platforms like Moment House.

Merchandise. Similarly, for generations, many artists have earned income from merchandise. Since much of that merch was sold while on tour, COVID-19 created a similar disruption. But COVID-19 also forced many consumers to shift their in-person purchasing habits to online retailers. The rise of drop culture and retailers like MSCHF paint a future for what music merchandise could be.

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs). This is the latest thing that the cryptocurrency people want you to believe in. NFTs are a method of creating and tracking digital goods that cannot be trivially duplicated, theoretically allowing artists to sell rare, expensive, digital goods whose authenticity can be confirmed by anybody.

#stream2own, which is the revenue model of the streaming site Resonate, where fans pay steadily increasing royalty rates for playing a song, until the ninth play after which the listener "owns" the song and subsequent plays are free. The royalties from the nine plays are calibrated to cost slightly less than purchasing a song on iTunes.

Digital downloads. Many artists have been won over by Bandcamp’s commission-free Bandcamp Fridays and see traditional single or album purchases as being the future of music.

Paid fan interaction. Musicians are flocking to platforms like Patreon, Cameo, or OnlyFans that allow them to sell an exclusive look into their lives or even 1-1 communication.

Fixed-quantity album sales. Who could forget when the Wu-Tang Clan produced the album Once Upon a Time in Shaolin and sold only one copy at $2 million to Martin Shkreli?

Whether from a revenue or a strategic perspective, none of these alternatives are even close to being a replacement for what CD album sales used to be—nor do they compare to what the streaming platforms are paying artists today. But however immature these options are today, they represent enormous potential markets for musicians to capitalize on. The potential gains outweigh whatever fractions of a penny the #BrokenRecord activists manage to gain from Spotify.

As a parting thought, the world of computer software went through some of the same struggles as the music industry. When people started pirating music, they also started pirating software.

On the other hand, many major software projects are open source, meaning the software’s code is free for anybody to download, use, or modify. Commercial open source software (COSS) vendors—like Red Hat and MongoDB—built multibillion-dollar empires by charging for support and services on top of a free open source product.

Hackers and Hobbyist software engineers rapidly adopt great open source products—eventually spreading adoption to large enterprises who pay top dollar for additional support, services, and products from COSS vendors.

The #BrokenRecord activists generally don’t like the sound of giving their work away for free—like open source software maintainers have been doing for decades. But the open source philosophy might be the key to building the next multibillion-dollar music empire.

Changelog

January 11, 2021: Minor formatting changes.

January 31, 2022: Minor formatting changes to support features in Substack’s new editor. Some rephrasing in the conclusion.

February 13, 2022: Minor formatting changes. Removed unnecessary links.

Of course, Spotify is not the only digital streaming platform. For the purposes of this piece, we’ll ignore streaming platforms owned by a large tech company like Apple Music, Google Play Music, Amazon Music, or the platforms owned by Tencent Music. For the tech giants, music is a tool that lets them sell hardware or other products—making the economic considerations more complex.

Gray has since clarified that they are not “the ‘Fuck Spotify’ crew” anymore, but it’s hard to see an actual change in the movement’s tone.

Some of the struggle is because Spotify prioritizes growth over profits, but the nature of consumer marketplace businesses is to grow or die. It’s not possible for more musicians to make more money on Spotify if Spotify had dramatically fewer users.

I agree.

"Choice is simultaneously both the highest form of thought control and the greatest weakness in any thought-control system." – The Architect, Matrix Reloaded

The problem is choice. Here is another option for musicians https://thatvideomag.com/live-entertainment-and-artist-development-program.