David Geffen is one of the most successful music and Hollywood entrepreneurs in history—long known as the “richest man in Hollywood.” He is known for a personal style that is both vulnerable and brash—making both friends and enemies equally as quickly. His do-anything-to-win attitude represents a style of entertainment businessman that dominated the twentieth century.

(I may earn money from links in this post to books on Amazon.com.)

David Geffen’s background

David Geffen was born in Brooklyn in 1943. He dropped out of three different colleges and then found his way into the mailroom at the William Morris talent agency. He left for the Ashley-Famous Agency, quickly leaving there to cofound what became a hugely successful artist management firm. Then he started a record label called Asylum Records in a joint partnership with Atlantic Records, which was eventually acquired in entirety by Atlantic’s owner Warner Communications.

Geffen retired from 1977 to 1980 because he was incorrectly diagnosed with cancer. He returned to the business in 1980 by founding the label Geffen Records, which was eventually acquired by music giant MCA for $550 million in stock. He continued to run Geffen Records until he left to cofound the movie studio DreamWorks SKG with Steven Spielberg and Jeffrey Katzenberg, until his departure in 2008. He has managed to aggressively invest the money from his business ventures, growing his net worth to nearly $8 billion dollars.

Lessons from his career

#1: Fake it until you make it

One of the most famous tales from his origin story is how he got into the William Morris Agency’s mailroom. He lied that he had a degree from UCLA because he knew he would not be hired without one.

When he got the job, the Agency sent a letter to UCLA to verify his degree. Geffen—taking advantage of his position in the mailroom—intercepted UCLA’s response that they didn’t know who he was. Then, he printed out a letter on fake UCLA stationary stating that he had a degree in Theater Arts. He mailed it to his brother Mitchell’s law office in Los Angeles, who then mailed it back so the letter would arrive with a Los Angeles postmark. David Geffen later came clean to the William Morris Agency, but only after he had proven himself there.

The subterfuge was worth it. The Agency kickstarted his career, and he would go on to describe the William Morris mailroom as “the Harvard School of Show Business—only better: no grades, no exams, a small stipend, and great placement opportunities.”

#2: Seek out great mentors, but never be afraid to leave them behind

Geffen had a knack for attracting the mentorship of entertainment moguls, starting with Nat Lefkowitz—an executive at William Morris. Geffen built a relationship with him by showing up to the office on Saturdays to work and grab lunch with him.

In May 1968, Geffen turned in his resignation to Lefkowitz to join his new mentor Ted Ashley at his Ashley-Famous Agency. Geffen stayed there less than a year at Ashley-Famous before deciding to cofound an artist management firm with business partner Elliot Roberts. Geffen and Roberts claim that by 1972 they were running the most successful artist management firm in the world.

Geffen would later become the protege of Ahmet Ertegun, the legendary founder of Atlantic Records. Ertegun would encourage Geffen to start what would become Asylum Records in a joint venture with Atlantic (by then a subsidiary of Warner).

As part of the deal, Ertegun would introduce Geffen to his next mentor—Warner CEO Steve Ross, who would become something of a surrogate father to Geffen. He would move beyond his relationships with both Ertegun and Ross when he sold his second record label—Geffen Records—to music industry rival MCA

#3: Keep going back to the negotiating table

David Geffen sold Asylum in exchange for Warner stock, which did not enrich him as much as he thought because Warner’s stock price subsequently fell in the early 1970s. Geffen complained so loudly about this that in 1973 Ross placated him by merging Asylum with fellow Warner label Elektra and promoting Geffen to run both of them. In exchange, for the remaining six years of Geffen’s employment contract, Warner would pay a $1 million salary and pay in cash the difference between Warner’s average stock price and the stock price when Asylum sold.

Geffen was notorious for returning to the negotiating table with Ross many times over the years. Ross’s priority was keeping Geffen within the orbit of the Warner empire, and was generally willing to be flexible on compensation to achieve that. Ross was known for treating his executives and artists with luxury, but ultimately he was not able to satiate Geffen’s stratospheric ambition.

#4: Share uncomfortably personal details in order to gain others’ trust

While he occasionally dated women—even almost marrying the musician Cher—David Geffen built his career as a gay man during a time in America when homosexuality was stigmatized. However, he often shared the secret of his identity with others as a sign of trust—while still nominally being in the closet to the public.

His frankness made some uncomfortable, but it provided a valuable counterweight to the more stereotypically capitalistic aspects of his personality. He finally came out to the public during a November 1992 speech at a AIDS Project Los Angeles (APLA) benefit dinner.

#5: Get great deals signed, even in the face of opposition

As Geffen’s clout as an agent rose at William Morris, he signed a client that would turn out to be monumental to his career—Laura Nyro. In addition to being her agent, Geffen put together Nyro’s songs into a small music publishing company called Tuna Fish Music that they would be fifty-fifty partners in.

Standing in the way of the deal was Nyro’s old manager Artie Mogull, who had several signed contracts with her that would have conflicted with Geffen’s deals. Additionally, in an effort to combat harmful conflicts of interest, the entertainment labor union AFTRA forbade talent agents like Geffen from owning music publishing companies. Geffen was undeterred—hiring famous entertainment attorney Dick Barovick to break Nyro out of her deals with Mogull. Additionally, he gambled that AFTRA and the William Morris Agency would not find out about Tuna Fish Music before he sold it.

It paid off when Geffen sold Tuna Fish Music to CBS for $3 million worth of CBS shares. Geffen had failed to break Mogull’s contracts with Nyro and ended up settling with him for $470,000, but the deal still turned Geffen into a millionaire at twenty-eight years old.

#6: Make big promises and see what happens next

David Geffen was infamous for meeting artists and making huge promises to them to get them to sign. Tom King’s book The Operator describes Geffen and fellow agent Todd Schiffman—both then working in the music division of Ashley-Famous—meeting with a rock group called Strawberry Alarm Clock:

“We’re going to get you six Ed Sullivan shows,” Geffen promised the band, “and we’re going to get you on Janis Joplin’s next tour.”

Schiffman, who was not in a position to be moralizing, was nonetheless shocked. “David, what are you doing? he said after the meeting. “Six Ed Sullivan shows? Are you kidding? Janis Joplin wouldn’t piss on these people! We’re not going to give them any Janis Joplin dates.”

“If they have another hit, we’ll get them one Ed Sullivan show, and we’ll get them a couple of dates on somebody’s tour. I don’t care,” Geffen responded calmly. “And if they don’t have another hit, well, fuck ‘em.”

#7: Use the industry press to put pressure on business deals

David Geffen wanted to start his own label in 1969 with famous music executive and mentor Clive Davis joining him. Davis was slow to make a move, so Geffen announced to publications Cash Box and Billboard that Geffen was starting a label. He exaggerated that he had been offered a deal from several companies. Despite the pressure from the announcement, Davis chose to stay at Columbia Records instead of partnering with Geffen.

In 1972, Warner Communications owned half of David Geffen’s label Asylum Records—and Warner CEO Steve Ross was exploring buying the other half. Geffen prepared for the negotiation with a media blitz, with a glowing feature in the Los Angeles Times and then a story in Record World titled, “It’s The Artist, Not The Company” where Geffen describes his “artist-oriented” strategy for bringing success to Asylum.

In early 1990, the Wall Street Journal revealed the various suitors in the running for purchasing Geffen Records—which in itself put pressure on all of them at once. Geffen himself was quoted in the piece saying (inaccurately!) that he was “not about to sell” Geffen Records. Many suspected that he also leaked a subsequent WSJ piece that Geffen Records had agreed to be acquired by Thorn EMI for $700 million in stock and cash. The story wasn’t true, but it succeeded in goading Warner’s Steve Ross in returning to the negotiating table. Instead, Geffen Records ended up being acquired by MCA for $550 million in stock.

#8: Don’t be afraid to pick up the telephone

David Geffen is a master of working the phone lines, acting as a conduit for industry gossip with the goal of shaping what his allies thought of his rivals. A 1993 profile by the Los Angeles Times says:

Geffen’s primary business tool, as always, is the telephone. He is a legendary talker capable of fielding an unrelenting torrent of calls, whether he is at his house, which is stocked with several multi-line phones, or traveling in his car, which is equipped with enough telecommunications gear to satisfy the Secret Service.

A 1985 New York Times piece covers the specifics of how David Geffen uses the phone to wheel and deal, building connections and sharing gossip with artists and record executives alike.

Resources

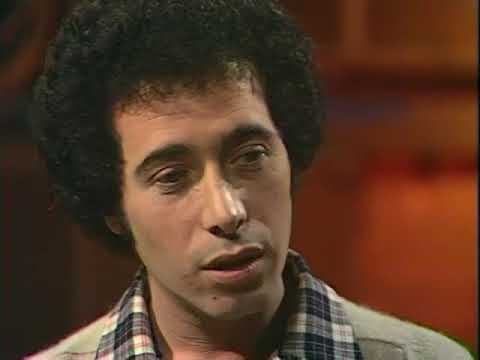

This is a video clip from an interview with David Geffen from a January 1978 episode of the British TV show The Old Grey Whistle Test, where he talks about the artist-friendly direction of the label.

Changelog

January 11, 2021: Minor formatting changes.

February 13, 2022: Minor formatting changes. Removed unnecessary links.

Thanks to Andrew Aldridge and Nikita Yurkov for reading drafts of this piece.