The music industry has long been home to interesting characters with shady business dealings. Especially during the twentieth century, many of these characters and dealings were connected with the Italian and Jewish Mob as a part of their larger business ventures.

(I may earn money from links in this post to books on Amazon.com.)

Why did the Mafia love the music business?

The music business was particularly appealing to the Mob for several reasons:

All-cash transactions. Many transactions were conducted in cash. Jukeboxes, entry covers, and drink purchases at nightclubs to vinyl at record stores to (sometimes) payments to artists. This allowed mobsters to hide profits tax authorities and launder money from other Mob operations.

Continual cash flow. The master recordings and publishing copyrights of hit songs are a source of continual cash flow, somewhat like (but more volatile than) rental properties or annuities. This ends up becoming a place to park capital accumulated from other Mafia-controlled businesses.

Cross-selling. Music businesses like nightclubs and record stores could be made into vendors of other Mafia-controlled businesses. The Mob could provide real estate, construction workers, food & drink, tablecloths, garbage collection, and more.

Ease of counterfeiting. Analog forms of music like vinyl records and cassette tapes were easy to counterfeit. Bootleggers could press counterfeit records and sell them at or below retail price for cash, effectively printing money.

Today, the Mafia’s influence on America has declined, and revenue in the music industry increasingly comes from digital sources, making it harder to launder money and avoid paying taxes and royalties.

Arguments against evidence of Mob influence

A handful of prominent names in the music industry have claimed that the connections between the music industry and the Mafia have been overblown. Jerry Wexler of Atlantic Records fame has said “the Mafia would like to control the record industry, but they have never managed to. They’re just on the fringes: selling cut-out records, pressing, independent promotion.” That is, mobsters were limited by their choice in taking on roles as managers, brokers, or financiers as opposed to more creative roles in a fundamentally creative industry. Former Sony Music Entertainment CEO Walter Yetnikoff has also widely criticized the conspiracy theories of Mob influence in the music industry, but in his memoir, he describes how much he knows of his friend and fellow label head Morris Levy’s Mob ties.

Music businessmen with Mob ties

(Editorial note: In this piece, I focus on businessmen as opposed to recording artists with mob connections, like Frank Sinatra. Additionally, I avoided including businessmen that tried to create a reputation for having Mob ties, but without much evidence.)

Meyer Lansky, the “Mob’s Accountant”

Depicted: Meyer Lansky (in front). Photo Credit: Al Ravenna, World Telegram staff photographer - Library of Congress. New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection.

The Jewish mobster Meyer Lansky is one of the most successful organized criminals in history. Lansky owned a large international gambling empire, but he also had significant investments in music jukeboxes. He was rumored to have run a company that “controlled every Wurlitzer jukebox in the New York area.” The book Meyer Lansky: The Thinking Man’s Gangster tells the story of Meyer Lansky’s rise to power.

The Chicago Outfit

Depicted: Some members of The Chicago Outfit. Photo Credit: American Mafia History.

The Mob history book The Outfit tells the story of the Chicago crime syndicate that rose to power under Al Capone. The book describes The Outfit’s involvement with both Meyer Lansky and the jukebox manufacturer Rudolph Wurlitzer Company. The book describes Wurlitzer’s vice president Milton J. Hamergren testifying before Congress that Wurlitzer Corporation knew that Lansky and his associates represented a solution to struggles that Wurlitzer was having when it came to distributing jukeboxes to bars—even admitting that they knew that people may have been killed in the pursuit of selling jukeboxes.

Jules Stein, Lew Wasserman, and MCA

Depicted: Jules Stein. Photo Credit: UCLA Stein Eye Institute.

Depicted: Lew Wasserman. Photo Credit: Documentary.org. Screen capture from Barry Avrich’s documentary The Last Mogul

The Outfit also had close ties with Jules Stein and his company, the Music Corporation of America (MCA). MCA would turn into a Hollywood giant under Stein’s protégé Lew Wasserman and would eventually split, merge and evolve into successor behemoth corporations like NBCUniversal and Universal Music Group.

The book The Last Mogul: Lew Wasserman, MCA, and the Hidden History of Hollywood describes MCA as founded by Stein and scaled by Wasserman. It draws a loose connection between Stein, MCA, and Meyer Lansky via attorney and Mafia fixer Sidney Korshak, who was one of the top Mob figures in Los Angeles. Korshak was one of Wasserman’s closest friends for decades until the friendship was no longer useful to Wasserman.

The book Dark Victory: Ronald Reagan, MCA, and the Mob alleges that Wasserman was the link between the actor Ronald Reagan and the Mafia, and was instrumental in funneling entertainment revenue to the Mafia while pushing Reagan into becoming President o the United States.

Morris Levy

Depicted: Morris Levy. Photo Credit: Richard Carlin

Morris Levy is one of the most notorious independent record label heads of the twentieth century. He started his career as a nightclub hatcheck boy, rising to become the owner of the popular Birdland jazz club on Broadway in Manhattan.

From there, Levy started Roulette Records as well as several other record labels and music publishing companies. He was infamous for having longstanding connections with the Genovese Crime Family, including the crime bosses Tommy Eboli and Vincent Gigante. Levy had used their money to finance his business ventures, with the mobsters starting as “silent partners” whose presence became increasingly visible as time went on, often conducting meetings for Mob-related business at Levy’s offices.

Morris Levy also acquired and grew a chain of record stores he renamed Strawberries. He allegedly purchased the chain in partnership with the Genovese crime family with the intention of the family eventually taking total control of the business and its cash flow.

In 1990, after having very openly been under FBI investigation for years, Levy was convicted of extortion but died two months before he was scheduled to report to prison.

The book Godfather of the Music Business: Morris Levy tells the story of Levy’s rise to power as a boss in the world of nightclubs, record labels, record stores, and other entertainment businesses. The autobiography Me, the Mob, and the Music: One Helluva Ride with Tommy James & The Shondells by musician Tommy James tells much of the same story from James’s perspective of being a recording artist on Levy’s Roulette Records.

“The Network” and the independent promotion scandal

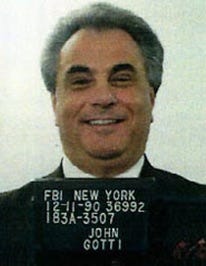

Depicted: John Gotti. Photo Credit: FBI

During the heydey of record stores and radio stations, record labels had a chicken-and-egg problem when it came to promoting new albums from their artists. Labels needed singles from their albums to play on radio stations to fuel album sales at record stores, but typically radio stations only wanted to play the music that was already in demand.

Over time, a process and culture for pitching radio stations—including paid bribery and payola—developed, allowing labels to pay to break new songs and artists. Over the twentieth century, the US Government made various weak or unsuccessful attempts at cracking down on payola in the music industry, but ultimately the crackdowns only facilitated to strengthen a layer of middlemen—known as The Network—between the record labels and the radio stations. The promoters of The Network managed the relationships with the radio stations while allowing some level of plausible deniability for record labels. By some estimates, by the 1980s anywhere from $60 million to $80 million per year was being spent on independent promotion for records.

Fred DiSipio, Joe Isgro, Dennis Lavinthal, Gary Bird, Jerry Brenner, and Jerry Meyers were all powerful players in The Network. These men, and the record labels and radio stations they worked with, are covered in Fredric Dannen’s groundbreaking book Hit Men: Power Brokers and Fast Money Inside the Music Business.

Dannen’s book describes an iconic moment in January 1986 when an undercover New York State Organized Crime Task Force agent bumped into an undercover FBI agent, both tailing John Gotti who was meeting with Fred DiSipio and Joe Isgroat at the Helmsley Palace Hotel on Madison Avenue in Manhattan. An NBC News camera crew led by Brian Ross happened to have been following Disipio, turning the meeting between the Mob men and the Network men into a nearly-seven minute NBC news segment that led to a federal grand jury investigating record label payola.

Joe Isgro, with two other defendants, was charged with 57 counts of offenses related to payola, but the case was dismissed due to prosecutorial misconduct. In 2014, Isgro was indicted in New York State Supreme Court on various gambling charges, revealing accusations that he is a member of the Gambino crime family.

Changelog

May 23rd, 2020: Set the image of Meyer Lansky as the image preview. Added some better formatting for image captions and the list at the beginning of the article.

January 11, 2021: Minor formatting and editing changes.

February 13, 2022: Minor formatting changes. Removed unnecessary links.