The dark history of the jukebox: how the Mafia used murder to build music machine empires

Organized crime never sounded so good.

For much of the twentieth century, the music industry was heavily influenced by the Mob. One of the pillars for their control was the jukebox—the innocent-looking coin-operated music machines that were common in diners, bars, and clubs until they began to fall out of favor in the 1970s.

Every jukebox was a cash business selling an ephemeral product, and it was easy for the jukebox owner to falsify how many songs were actually sold, making the jukebox an ideal tool for money laundering and tax evasion for venue owners and organized crime.

(I may earn money from links in this post to books on Amazon.com.)

The origins of the jukebox

Thomas Edison invented the phonograph in 1877, which Louis Glass and William S. Arnold modified in 1890 to make it coin-operated. Albert K. Keller claims to have invented a coin-operated phonograph first, but Glass and Arnold were the first to do a public demonstration. Keller managed to get a head start on marketing coin-operated photographs anyway until the arrival of the “Big Four” jukebox manufacturers—Automated Musical Instruments (AMI), Seeberg, Rock-Ola, and Wurlitzer.

Some of the manufacturers had Mob ties. Rock-Ola was founded by Mob-connected businessman David Cullen Rockola, who was charged with corruption in 1929 but only served six months by turning State’s Evidence against James “High Pockets” O’Brien and other mobsters. For some time, AMI was run by Chicago mobster Jake Guzik’s son-in-law Frank Garnett and then taken over by mobster Sam “Mooney” Giancana in 1949.

Depicted: A mid-twentieth century Wurlitzer jukebox. Photo Credit: Joe Mabel.

These manufacturers typically did not sell jukeboxes directly to bars and clubs—instead selling to regional distribution companies, who in turn would sell to operators of jukebox “routes” that contained groups of venues. Jukebox routes, distribution companies, and operators’ associations became a natural toehold for mobsters to enter the jukebox market.

The Mob moves into jukebox distribution

However, the Mob—in Chicago, at least—did not play much of a role in jukebox distribution until Mooney Giancana partnered with African-American hustler Eddie Jones. Jones and his brothers distributed jukeboxes and also ran “policy”—the illegal lottery played by many Black Chicagoans. Giancana eventually kidnapped and then forced Jones to exile to Mexico—all in order to take control of Jones’ business on behalf of the Mob syndicate known as the Chicago Outfit.

Depicted: Sam “Mooney” Giancana. Photo Credit: Unknown.

From then on, various mobsters started or joined various distribution companies around the country, including:

Lormar Distributing Company—run by Mooney Giancana’s underlings Bill McGuire and Charles “Chuckie” English.

Century Music Company—run by mobsters Jake Guzik and Dennis Cooney. By 1954, Century Music “was believed to control more than 100,000 of the nation’s 575,000 jukeboxes.”

Runyon Sales Company—owned by the gangster Abner “Longy” Zwillman. Runyon distributed AMI jukeboxes on the East Coast.

Riverside Music Company— co-owned by Longy Zwillman and Mike Lascari.

Chicago Simplex Distributing Company—run by Alvin Goldberg, Joe Accardo, and Frank Garnett.

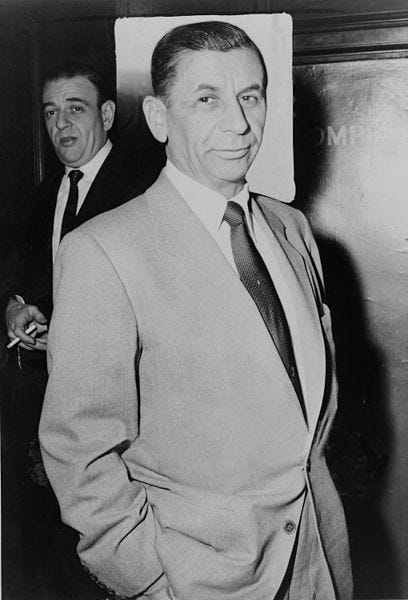

Emby Distributing Company—cofounded by a group that included Alvin Goldberg and the international Jewish mobster Meyer Lansky. It is said that—for a time—Emby controlled “every Wurlitzer jukebox in the New York area.”

Depicted: Meyer Lansky. Photo Credit: Al Ravenna/Library of Congress.

In 1946, Emby would sell its Wurlitzers for $1080 per machine to the operators of jukebox routes that would place them in their territories’ bars and clubs. Route operators might control a few hundred machines each. They would supply repairs and new records for 50% to 70% of the take, which could go up to about $15 per machine per week in New York. Emby worked to cut out the “route” middlemen that stood between Emby and venue owners—often by acquiring failing routes and often using intimidation, threats, and picketing from false-flag labor unions made up of paid actors.

Milton Hammergren’s testimony

In 1958, Milton J. Hammergren, former Vice President and General Sales Manager for the Wurlitzer Corporation, testified in front of a Congressional committee. Hammergren was questioned by then-Committee counsel Robert F. Kennedy about the Wurlitzer Corporation’s knowledge of and dependence on Mob-affiliated distributors:

HAMMERGREN: […] Yes, there was violence, such as blowing out the windows of the store or blowing up an automobile or something of that nature, or beat a fellow up.

KENNEDY: Is that part of the characteristics of the industry?

HAMMERGREN: Yes; I would say so.

KENNEDY: Were there also killings?

HAMMERGREN: Yes, there was.

Hammergren went on to describe the murder of Lehme Kelley—an operator of around seven hundred jukeboxes in the Joliet, Illinois area. Kelley’s brother Dennis was also killed shortly thereafter. Kennedy continued his questioning:

KENNEDY: Were company officials upset about the use of force?

HAMMERGREN: Company officials, of which I was one, yes, we didn’t like it, but we still had to sell jukeboxes. We knew all about it, and we knew what the problems were. We tried to go along with it the best we could.

[…]

KENNEDY: I mean if somebody, just in the course of trying to get your boxes distributed, if somebody was killed, that was taken as part of the trade?

HAMMERGREN: That is one of the liabilities of the business, I would say.

Using jukeboxes to promote music careers

Once having gained control of jukebox distribution, the Mob could control which records would be selected to go into the jukeboxes, offering jukebox placement to promote artists of their choice.

Carol Lawrence (born as Carolina Maria Laraia) unknowingly benefited from Mob promotion. Her father Mike Lairia was connected with mobster Joe Accardo, who placed Carol’s debut record into thousands of Mob-controlled jukeboxes. Carol later went onto play various roles in theater and television, including Maria in the musical West Side Story on Broadway.

Depicted: Carol Lawrence appearing on the TV show General Electric Theater. Photo Credit: General Electric Corporation

The journalist David Leon Chandler, in his book Brothers In Blood, wrote how then-Lousiana Governor Jimmie Davis helped local Mob boss Carlos Marcello open casinos in New Orleans. In addition to being Governor, Davis was also a country singer. After this favor, Davis’s recording of the song “You Are My Sunshine” suddenly appeared in various Mob-controlled jukeboxes around the country. Twenty years later, the FBI dredged nearly one hundred thousand records from the East River—most of them being copies of Jimmie Davis’s “You Are My Sunshine.” The FBI came to the conclusion that the discarded records had been originally bought by the Mob and placed into jukeboxes as payment for Davis helping the casinos open.

The Chicago Outfit also used its control over jukeboxes to promote acts booked by Jules Stein’s Mob-connected Music Corporation of America (MCA). Boosted by jukebox promotion, these acts would go on to perform at Mob-controlled venues or even sign to Mob-owned record labels. When the Mob could not own the recording or publishing for these artists, they would monetize these artists’ popularity by printing and selling counterfeit records.

Finally, because self-reported jukebox play data was part of the dataset used to determine the Billboard Hot 100 (until 1959) and which records radio stations chose to play as their Top 40, the Mob could promote artists of their choice by falsifying jukebox play data.

Meyer Lansky’s failed bet on television

Over time, it became impossible for the Wurlitzer Corporation to play dumb about their dependence on the Mob for distribution. The Wurlitzer Corporation eventually asked Meyer Lansky to leave Emby Distribution. Lansky acquiesced and moved on from Emby to cofound Consolidated Television in 1947 with partners Ed Smith, Bill Bye, Joe Adonis, and Frank Costello.

Consolidated Television sold television sets to the same bars and clubs that bought Emby jukeboxes. They also wanted to produce “soundies”—the name for early music videos—to give bar and club patrons something to watch on the TV sets. The venture went out of business in less than two years for multiple reasons including:

A lack of recurring revenue. Jukeboxes provide continual revenue and require continual maintenance and new records. In contrast, televisions weren’t coin-operated and did not need servicing to get new content.

Poor product quality. Consolidated Television’s TV sets continually broke down, leaving venues unhappy and adding continual manufacturing and repair headaches for Consolidated Television.

Competition from home-installed TVs. Consolidated Television was a bet that Americans would go to bars to watch TV. Instead, many Americans chose to purchase a TV set for their living room and stay home at night to watch it. Meyer Lansky later said, “We should have gone into the home-end set, and maybe I would be a very rich man today.”

The Scopitone and the mobsters behind it

The Scopitone was a coin-operated video jukebox that appeared at the start of the 1960s and was all but gone by the end of the decade. The Scopitone was made by CAMECA—a Parisian subsidiary of the French electronics giant CSF Corporation—in 1960 as a superior version of an older video jukebox called the Panoram made by the Mills Novelty Company in Chicago. (Today, CAMECA is a maker of scientific instruments.)

Depicted: A surviving Scopitone machine. Photo Credit: Joe Mabel.

The typical Scopitone film was a three music video on 16mm color film and a magnetic soundtrack, featuring barely-clothed B-list recording artists and film stars gyrating in front of equally scantily-clad backup dancers.

Depicted: Joi Lansing’s Scopitone music video for her song “The Web Of Love.”

In 1961, the William Morris Agency talent agent George Wood began putting together a deal to bring the Scopitone to America. Wood formed a company called Scopitone Inc, which would have the American rights to the Scopitone machine, backed by a consortium of Mob-friendly investors including Genovese crime family capo Vincent “Jimmy Blue Eyes” Alo and underboss Gerry Catena.

The entire time, the NYPD and the District Attorney’s office had bugged Wood’s office and wiretapped his bachelor pad’s telephone in an effort to collect evidence and turn him against the mobsters. But in November 1963, Wood was badly beaten up during a night at the Camelot Lounge and died after checking himself into Mount Sinai the next day. The District Attorney’s office lost their potential witness, but another William Morris agent closed the Scopitone deal.

In 1964, Scopitone Inc was unable to import enough Scopitones from France, so they started looking for an American company that could manufacture more. They cut a deal with the publicly-traded plastic sign manufacturer Tel-A-Sign Corporation to build thousands of Scopitones, with Tel-A-Sign ending up with an eighty percent stake in Scopitone Inc.

The Genovese crime family’s involvement in the deal attracted the attention of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) as well as US Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. The US Government launched a secret grand jury to investigate Tel-A-Sign. An April 1966 Wall Street Journal article leaked the news of the grand jury investigation, which sent Tel-A-Sign into a tailspin. The CEO resigned a few weeks after the Journal article. Scopitone Inc filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 1967 and then shut down completely in 1969. The machines were sold off and found other purposes—many of them used to give peep shows. The Justice Department ended up charging nobody with a crime in direct relation to the investigation—other than Vincent “Jimmy Blue Eyes” Alo for making false statements to the SEC.

The jukebox in modern times

Technogical and social change caused jukeboxes to begin falling out of favor as early as the 1960s. Today, user-selected music in live venues is dominated by companies like TouchTunes and Rockbot. The selection of available music is much wider than could have ever fit in a traditional vinyl or CD-based jukebox.

But for the most part, the era of the barroom jukebox is dead and gone.

Changelog

January 11, 2021: Minor formatting changes.

February 13, 2022: Mild formatting changes. Removed unnecessary links.

As a grandson of one of the surviving brothers, it was Leahm Kelly, to spell it correctly. The 2 surviving brothers were Glenn, my grandfather, and Stanger, his liquor store is still called Kelly's in Joliet. Fascinating article, growing up we heard so many different stories of what happened, my dad's cousin was in the back seat when her father was murdered.