The wall between record labels and music streaming platforms is about to collapse

How TikTok and UnitedMasters are about to change the balance of power in the music biz.

For a long time in the history of recorded music, there has been a wall between the IP-owning businesses like record labels and the platforms that offer music to listeners— everything from radio stations to video streaming sites.

Over the years, music businesses on one side of the wall or another have tried to punch a hole through it. Frederic Dannen’s classic book Hit Men describes the long history of bribery from record labels to radio stations, often facilitated by independent promoters with connections with organized crime. The US Government’s efforts to crack down on payola were largely unsuccessful, but fear of government intervention ended up strengthening the wall between the businesses who own music and the businesses who play music.

Today we’re going to look at two important questions for understanding the wall:

Why can’t record labels or publishers start their own music streaming site?

Why can’t streaming platforms sign artists like a label?

And why the wall might collapse for good.

(I may earn money from links in this post to books on Amazon.com.)

Why can’t record labels or publishers start their own music streaming site?

THE SHORT ANSWER: They are justifiably afraid of the government.

If the major record labels were to start their own direct-to-consumer platform, they would risk becoming victim to antitrust action. In fact, they nearly have.

In 2001, Sony Music and Universal Music tried to create their own online music store called PressPlay as a counterweight to rapidly-growing Internet piracy. Not only did the store fail to gain traction, but it attracted an official inquiry from the US Department of Justice (DOJ).

Depicted: A downsampled screenshot of PressPlay—taken in the year 2002—showing a search results page for “dave matthews.” Photo Credit: Steve McCannell for OpenP2P.

The DOJ has begun to take another look at the music industry. Last month, the DOJ held a workshop examining competition law around public performance royalties—it’s hardly a shot aimed directly at labels or publishers, but there is no telling who is next on the docket.

The risk of antitrust action might be low, but history has shown that the potential losses are enormous. The American film industry was terraformed by the 1948 US Supreme Court decision United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc. The decision nearly eliminated the Hollywood “studio system”—referring to the near-total control that movie studios had over both their talent and their film distribution. No large player in the music industry can afford to attract that level of government interference.

Why can’t streaming platforms sign artists like a label?

THE SHORT ANSWER: No platform can sign talent without angering labels/publishers and risking access to existing catalogs of hit songs.

The users of platforms like TikTok, Spotify, YouTube, and so forth expect access to the greatest hits in major label catalogs—there is no substitute for the most iconic songs. But for the platforms, the unknown gains of signing new talent isn’t worth the loss of existing catalogs for these platforms.

For platforms like Spotify, the threat of rightsholders pulling their catalogs is a real one, although the catalogs usually return a few years later. A few notable examples:

In 2011, the music distributor STHoldings pulled music from more than two hundred record labels that they distribute.

In 2014, Big Machine Label Group pulled Taylor Swift’s catalog from Spotify. However, Swift relented and her catalog returned to Spotify in 2017.

In 2017, Jay-Z removed most of his catalog from Spotify—in part to entice listeners to TIDAL, the streaming site that Jay-Z co-owns. However, he returned his catalog to Spotify in 2019 to celebrate his fiftieth birthday. Similarly, Jay-Z’s wife Beyoncé’s album Lemonade was exclusive to TIDAL until three years after its release.

In 2019, the Indian record label Saregama India Ltd pulled their songs from Spotify for Indian listeners. The catalog returned to Spotify a year later.

The fact that music usually returns to Spotify might suggest that they have the upper hand in the licensing negotiations. But based on the absence of drastic catalog removals initiated by Universal Music, Sony Music, or Warner Music, we can assume that the status quo is very favorable to the labels.

(On the other hand, there is not a comparable tension in the podcasting world. When Spotify signed the podcaster Joe Rogan for more than $100 million, I wrote a piece detailing why Spotify can pursue this aggressive strategy in podcasting but not music.)

So then, what are the cracks in the wall?

The answers to the above two questions are generalizations. They hardly describe the motivations of every single entertainment executive—and cracks in the wall have been spreading over the years.

Here are some of them:

Major labels founding the video streaming site VEVO

Six years after PressPlay shut down, the labels were ready to try again in directly serving content to music fans. Universal Music, Sony Music, and EMI started VEVO in 2009 as a joint venture, with Warner Music joining in 2016. The original goal for VEVO was to be a high-end music video streaming service, modeled after the TV and movie streaming site Hulu—which was similarly launched as a joint venture between NBCUniversal, News Corporation, and later Disney.

Ultimately, the vision failed. VEVO’s website and mobile app never gained traction. Today, VEVO’s mark is ultimately a set of YouTube channels. The dream of owning users’ eyeballs—as opposed to giving them to Google—didn’t work out.

While the Department of Justice never launched a formal inquiry into VEVO like they had into PressPlay, antitrust was allegedly a continual concern. It is rumored that Universal Music and Sony Music invited Abu Dhabi Media Company in as an investor in VEVO in order to minimize antitrust concerns.

Major labels investing directly in Spotify

The major labels presumably learned from PressPlay and VEVO that platforms are easier to buy than build. The founding and rapid growth of Spotify—independent of the labels—provided the labels a financial opportunity that could never have been realized by PressPlay or VEVO with theoretically lower antitrust risk.

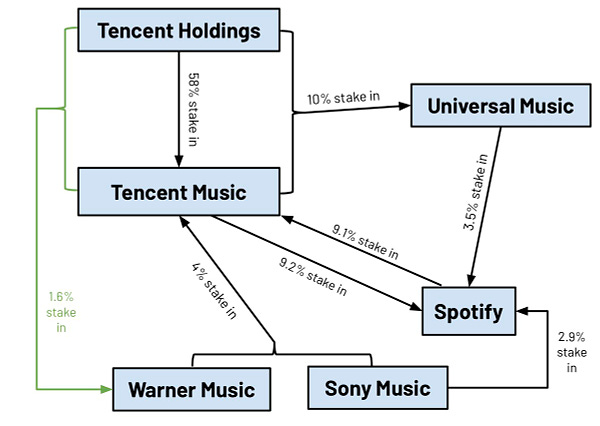

Not only is Spotify’s core business dependent on catalogs from the majors, but the majors are directly invested in Spotify itself. The music journalist Cherie Hu periodically graphs some of these relationships:

Major labels running their own playlisting companies.

The major labels buying stakes in Spotify gives them access to Spotify’s financial upside, but it doesn’t give them the type of editorial control that they could have had if PressPlay or VEVO succeeded.

Music streaming sites like Spotify and Apple Music have a considerable amount of power when they decide which songs end up in their human-curated or algorithmically-generated playlists. A relatively-unknown track might find its way to millions of listeners at once—turning it into a hit overnight.

Over the past few years, the major labels have created their own playlisting companies to capture some of that editorial direction for themselves. Universal Music owns Digster, Warner Music owns Topsify, and Sony Music owns Filtr.

Major labels entering music distribution.

Independent artists typically do not upload their music directly to platforms like Spotify. Instead, they use distribution services like Stem, UnitedMasters, or DistroKid. These distributors have a lot of data about which independent artists are exploding in popularity—which is useful for labels that are looking for artists to sign. Amuse is a company that offers free distribution in order to collect data about artists that they could sign to their in-house label.

The Big Three record labels have made big investments into music distribution—theoretically allowing them access to tremendous amounts of data:

Universal Music Group launched the distribution service Spinnup—first in Sweden in 2013

Warner Music Group launched their own distributor Level Music in 2018.

Sony Music Entertainment bought the music company The Orchard. However, The Orchard is more selective about whose music they distribute when compared to DistroKid or Spinnup.

TikTok’s new deal with UnitedMasters.

If TikTok were to try signing their own talent, they might agitate rightsholders. Or they may not. We can’t know without them trying.

But in either case, this week TikTok announced the next best thing to signing their own talent: a new deal allowing artists on TikTok to use UnitedMasters to distribute their music to Spotify and other platforms.

UnitedMasters is more than just a music distributor. They offer (some) artists licensing opportunities and brand deals, like their continually-changing soundtrack for the basketball videogame NBA 2K. Rapidly rising artists like NLE Choppa and Lil Tecca signed to UnitedMasters as if it were a major label, although both have since left in favor of traditional label deals.

The beauty of the TikTok/UnitedMasters deal is that it offers a career path for TikTok artists similar to signing to a major label, but in a manner that is less likely to anger rightsholders. TikTok presumably isn’t doing any signing themselves, and UnitedMasters presumably is not dependent on record labels or music publishers for their catalogs. When both of these companies combine their strengths, the “wall” practically disappears.

The streaming site Quadio launching their own record label

Depicted: A screenshot of the Quadio Records homepage, featuring their initial roster of five artists. Photo Credit: James Mishra

Quadio is a niche music streaming site focusing on helping college students discover up-and-coming musicians on campus. This week, they launched their own in-house record label Quadio Records with an initial roster of five artists.

This arrangement works out because listeners do not use Quadio to listen to established artists. Quadio centers around listeners discovering nearby unsigned artists—which means that it can collect data about artists on the platform, sign the most promising artists, and then use their platform to promote their signees. Because they are opting out of the rest of the music market, Quadio has nothing to lose and everything to gain from vertical integration.

So where is this all going?

When it comes to antitrust concerns, the future is unclear. It heavily depends on who is going to be the next President of the United States. But the Big Three record labels have managed to chip away at the wall with their investments in distribution, playlisting, and platforms like Spotify and VEVO.

On the other hand, the negotiating positions for platforms like Spotify and TikTok is likely to strengthen over time if future music is routed through independent distributors like Stem or UnitedMasters versus the three major labels. Perhaps Quadio’s recent record label is a glimpse of what one of the larger players in the market might be able to do.

Changelog

January 11, 2021: Minor formatting changes.

February 13, 2022: Minor formatting changes. Removed unnecessary links.